We build community in weekly workshops, artist-in-residence opportunities, and a summer Media Academy hosted by Madison Public Library, as well as related courses at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Making Justice uniquely incorporates diverse community members to engage underserved youth as part of a maker program, rather than a maker space with high-tech equipment.

Evolving from pilot programs for youth under the supervision of the Dane County Juvenile Court Program, the initiative now serves a broad demographic of community members who engage in collective learning. Making Justice has become a program generator by providing support to community members interested in developing learning initiatives, enriching educational opportunities at Madison Public Library, the Madison Metropolitan School District, and University of Wisconsin-Madison.

What we do interweaves our voices as part of an ongoing dialog that sustains community building within and beyond Making Justice. Check out our Authors page to learn more about the contributors to this curated community article.

Program Platform

Nancy: Which programs should we include in Making Justice? There seem to be new programs and partnerships continually spinning off. In fact, you could describe Making Justice as a program generator.

Jesse: And it’s amazing how each new partner creates their own flavor for the different programs we run. That’s something I’d like to highlight, because it’s not the traditional library route. It’s a whole different world when librarians realize that we don’t have to devise everything ourselves, that we can bring all these other people in, these new ideas and resources. If it were just our library team doing these programs, with no community input or community partners, it would suck.

Nancy: Let’s focus here on how we built Making Justice as a program platform that supports community members interested in developing learning initiatives for underserved teens. In other sections we’ll detail our partnerships, goals, and methods—who we are, why we do it, and how we do it.

Jesse: Note that it took time to build this platform. All the efforts that were put into those first two years to build a foundation, it’s a huge piece that deserves attention. It took a long time for people to understand and appreciate that. But it’s totally obvious to everybody now.

Nancy: And we should point out a significant difference between Madison Public Library’s Bubbler and Making Justice programs, particularly during our launch years from 2014-16. Both are exceptional as maker programs, rather than maker spaces for high-tech equipment. But Bubbler programs were predominantly planned by white library staff, artists and makers for participants who typically included young white professionals, students and families. Making Justice workshops incorporated diverse community members to engage underserved youth, who were overwhelmingly from communities of color; see Who we are for details.

Grant report: Making Justice builds on an emerging maker movement described as a “new industrial revolution” that has “democratized the tools of both invention and production.” Critics have argued that makerspaces are not as equitable or revolutionary as commonly portrayed, dominated by privileged white male hobbyists and often connected with corporate interests.

Pilot Programs

John: Refresh our memory, Nancy and Jesse. What was your intent when you launched the program?

Nancy: Actually, Making Justice was a 2014 spin-off from pilot programs that opened community doors at both the library and UW-Madison.

Jesse: Yeah, we did the uCreate Project for teens at the Dane County Jail beginning in 2010. The idea was to use cutting edge digital media to connect incarcerated teens in Madison, New York City, and Charlotte NC. And then in 2012 I began a Bubbler stop-motion animation program for underserved teens, in collaboration with Community Partnerships, Inc., Centro Hispano Com Vida and the Dane County Juvenile Court Program. The workshops were here and there to begin with, not on a weekly basis.

Nancy: That’s when I reached out to John at the Juvenile Court Program, when I was developing my UW Legal Studies course Looking Beyond the Law’s Letter. I wanted to help my undergrads get a better understanding of the juvenile justice system, to learn what it was like to be entangled in the system, particularly the racial disparities. I was riffing off equity—the prerogative to look beyond the law’s letter for the common good—which informs juvenile justice. And I wanted to incorporate media arts, alternative literacies. So I partnered with Kay DeWaide at Community Partnerships, who had created expressive ArtSpeak workshops. Here UW undergrads and teens in the system could connect as they developed media art projects. And then I heard about what Jesse was doing and thought “Oh, I need to talk to him.”

Jesse: I met Nancy when we were finally at the point of offering animation workshops on a weekly basis in 2013. And she’s like “Can I come with?” And I said “Yes, please! Help us figure this out.”

Nancy: I was really excited to learn more about teaching with digital technologies in Jesse’s animation workshops. We used more traditional media in the ArtSpeak workshops, like drawing, painting, and collage. Only my undergrads had the opportunity to experiment with digital technologies, back at UW, not the teens.

But I was frustrated by the endless critter smash-ups that the teens were animating. Jesse gave them small plastic objects – dinosaurs, ninja turtles, human figures—to use in their stop motion videos. Inevitably, the teens staged a battle. I wanted to encourage more creative, reflective, and expressive content. The ArtSpeak teens had developed amazingly creative and personalized content. Because Kay was trained as an expressive art facilitator, and really knew how to connect with the teens, to help them open a door within themselves.

Weekly Workshops

Nancy: Making Justice officially launched in 2014, building on our pilot programs and partnerships. Project-based workshops were offered at 3 locations each week, paired with a UW community-based learning course. We originally invited community members to help develop and facilitate workshops at the Neighborhood Intervention Program. During our second year, we expanded community-led programming to all our workshop locations.

Teen participants were primarily youth of color from underserved communities. UW students came from different departments, mostly library and legal studies. All created graphic and 3D art, photographic, spoken word, storytelling, performance, video, culinary and exhibit projects documenting themselves and their communities. Our partnerships, which greatly expanded after 2014, originally included Madison Public Library, UW-Madison, Community Partnerships, Inc., and Dane County’s Neighborhood Intervention and Juvenile Court programs. Grant funding for the first two years was provided by UW’s Ira and Ineva Reilly Baldwin Wisconsin Idea Endowment and the Morgridge Center for Public Service.

Grant application: Making Justice will address the nation’s widest black/white educational achievement gap and highest per capita black juvenile arrest and incarceration rate in Dane County, Wisconsin. The initiative will advance the Wisconsin Idea that the university should improve people’s lives beyond the classroom.

Jesse: We originally planned to serve 200-250 teens annually in the weekly workshops. In fact, we worked with closer to 750 teens over the two-year grant project. Hey Marta, what’s the current attendance at the weekly workshops?

Marta: We currently serve over 500 teens on an annual basis.

Nancy: The most important demographic is the over 50 community partners—a majority representing communities of color—who helped develop, facilitate and evaluate Making Justice during the two-year grant period, more than seven times the number of projected partners.

Grant report: Teen voices and creative work are showcased on a Teen Bubbler website created by program staff in collaboration with Design Like Mad, an organization that pairs professional designers with nonprofits to address design problems in 12-hour marathons.

Program highlights include a collaborative mural for the Juvenile Detention Center, created at three separate locations; a Making Repairs session in UW’s Design Lab that partnered UW students and teens in stitched projects; a session at the black barbershop JP Hair Design featuring haircuts, production of the community news program Behind the Chair, and afterschool job offers; VIP seating at Bryan Stevenson’s UW Just Mercy presentation; a Cinco de Mayo themed meal created by teens to share with juvenile court administrators, judges, prosecutors, and defenders; and the exhibit Direct Message featuring larger than life-size teen self-portraits and statements on the Central Library façade.

UW Community-Based Learning Courses

Heather: I think it would be interesting to know how UW-Madison is tied in.

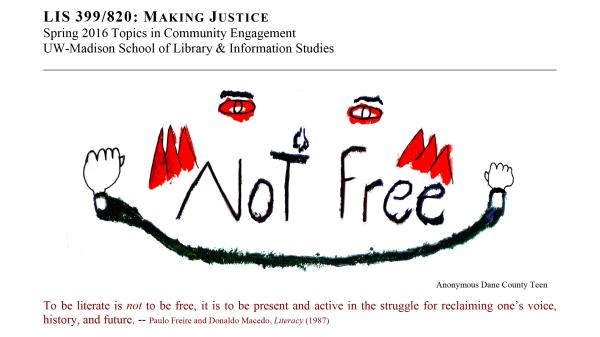

Nancy: The university offered a community-based learning course each semester during the 2014-16 grant period. Here’s a syllabus blurb: This course will facilitate learning outreach initiatives in Dane County. A core course concern is the relationship between power, knowledge and information for low-income communities of color. Students will learn how to develop, implement and evaluate an outreach initiative while engaging with a diverse underserved neighborhood. Biweekly seminars will address the racialization of disadvantage and crime; the school-to-prison pipeline; Hip Hop and the politics of illiteracy; library makerspaces and the production of knowledge; the curation and interpretation of community archives; and community-based evaluations of learning. Seminars meet in DesignLab, where students will experiment with a variety of information technologies, building alternative literacies. Practicing creative and collaborative problem solving, we will help reclaim voices, histories and futures, making justice in Dane County.

The number of students seeking Making Justice placements was more than double what we anticipated. So we created additional placements at libraries and community centers in underserved neighborhoods, where students helped develop a Minecraft club, STEM programming, and a food pantry.

Heather: But is UW still tied in, or is Faisal the only connection?

Veronica: We have gone through several different iterations.

Jesse: Faisal is currently the only direct faculty link. He can only offer his related UW course as an add-on to his full-time teaching commitment, it’s not supported by the university. He does it for free, on his own time.

Nancy: So Faisal recently offered a UW course, but there hasn’t been one every semester since I left UW in 2016?

Jesse: Correct. We’ve also had undergrads involved as volunteers, some from Edgewood College, during semesters when there aren’t any courses offered, but they haven’t received credit for the experience.

Nancy: I tried to recruit other UW faculty members for Making Justice, particularly black faculty, but it was hard, like pulling teeth. First of all, UW doesn’t have a very diverse faculty. The university wants to promote diversity, but they don't have the faculty to support it. Plus they prioritize research, not service. Edgewood College may be a better match for Making Justice, since community service is a requirement for all students and tenure-track faculty.

Jesse: That's why you guys are really lucky to have Faisal, because he is being recognized by the university right now, even if he’s not being paid for the time he gives to teaching his related UW course. And he has a lot to say about that. Tenure track should not only be research based. There’s this kid who’s calling Faisal “dad” now. He’s spent 14 weeks in workshops with Faisal, one night a week, but he doesn’t have a dad in his life. Now Faisal’s his father figure. There’s no way research is ever going to get that kind of impact. Faisal’s goal is to affect one kid each year, and he’s exceeding his goals ten-fold. He doesn’t get paid for it, the university doesn’t recognize it, but he’s fighting for it.

Faisal: I’ve been giving the university a hard time, talking with senior people regarding the Wisconsin Idea and who are the main beneficiaries. I’ve been at UW three years and I’ve learned that people who look like me - their lives have not been influenced beyond the boundaries of the classroom.

Veronica: That's why we were lucky to have Nancy...because she connected us with Faisal.

Nancy: That was the one of the most important things I did. I will take credit for bringing Faisal on board. Not only has Faisal brought greater diversity to UW courses offered in conjunction with Making Justice, he’s also helped the teens develop regular exhibits featuring their artwork and personal statements. These exhibits have powerfully engaged the teens and their families, as well as the greater Dane County community.

Grant application for exhibit related to Faisal’s 2016 UW course: “FauHaus II will create a racially diverse learning cohort from within and beyond the academy, prioritizing relationship-building and peer-supported learning. UW-Madison students and Dane County teens will collaboratively develop a socially engaged art exhibit under the guidance of faculty member Faisal Abdu’Allah, an internationally exhibited visual artist and barber whose work repositions black cultural identity. Referencing the legendary Bauhaus—a space where multiple disciplines were encouraged to flourish side by side—FauHaus II builds on the 2013 UW-Madison art laboratory and exhibit FauHaus: Bodies, Minds, Senses and the Arts and Making Justice. FauHaus II participants will collaboratively design, produce and install a public art exhibition.

Jesse: Faisal’s become a powerful voice at UW for engaging with the community, which is really wonderful, although it also limits his time. Now he’s trying to figure out how he can have the greatest effect on the community at large, but he has committed to Making Justice for the long run.

Faisal: People at the university are now interested in makerspaces and working with the community. I’ve put in some proposals. So see me at the doorway to that.

Artist in Residence

Jesse: The Making Justice Artist-In-Residence series brings a local artist to the Juvenile Detention Center or Shelter Home to offer a more in-depth teen learning experience, exploring a specific genre. It’s separate from the Bubbler's official Artist-In-Residence program, which takes place in library buildings. When possible, we provide Making Justice residencies during public school vacations, while teachers are away.

Our resident Making Justice artists have included local hip hop artist Rob Dz, who has offered music production and personal branding workshops (check out Rap Sessh for examples of teen productions); Carlos Gacharna, a Colombian artist who created a Juvenile Detention Center mural and Black Light Chalk workshops to engage teens in the study of chemistry and light; and Victor Castro, who worked with teens to create an ARTinside social sculpture project from inorganic debris—such as juice cups, milk cartons, and cereal containers—transforming empty spaces at the Juvenile Detention Center.

Rob: I work with teens on using music or poetry or word as a form of positive self-expression.

Making Justice has allowed me to really concentrate on offering kids what I feel my gift is, and to have them retain that. When you see the light bulb go off in their head through the platform that I’m offering, it’s kind of a dope thing. I didn’t really know how much I was going to be able to do what I do. But once I got in and was able to figure out how it correlated with Making Justice, I think it made for a very super dope relationship. And it’s still going forward, so obviously we’ve found a groove together.

Nancy: I think that you’ve connected over a longer period of time with kids who’ve been in the program than anyone else, because they’re coming back to you in Media Lab, the Bubbler’s free space for exploring digital media production.

Rob: Right. And that’s been a cool thing. Kids in detention would say “Yo man, when I get out I’m gonna come see you.” And then all of a sudden they’re showing up at Media Lab and “Hey, ‘member when I said I was comin’ to see you?” It’s been a cool experience for that to happen. This is what we work for, because this is that alternative to something else, you know what I’m sayin? That’s the whole purpose of Making Justice is to come in and offer this in hopes that it will keep kids from the potholes that they sink into.

Media Academy

Jesse: Media Academy is an important piece of what has spun off from Making Justice. The academy gives teens an intensive summer opportunity opportunity to work with music and film industry professionals, developing and publishing content promoting social justice. It was Rob’s idea after several stints as a workshop facilitator and resident artist. He asked what was next for these kids, and came at me with a five-minute pitch.

Rob: I wanted to work with teens from Making Justice for eight weeks during the summer—four days a week, three hours a day. They were getting one-off 90-minute sessions in our workshops, and they wanted to do more when they came to see me in Media Lab.

Jesse: And I was like “We’re absolutely doing exactly what you just said.” So then I looked for money and brought other people on board. We targeted kids from Making Justice workshops who showed the most interest and talent, inviting them to apply and helping them with the application process.

In our inaugural Summer 2017 Media Academy, we paired teens with adult mentors to work on group and self-guided digital learning projects. They produced several songs and music videos; Around the Way, a documentary on homelessness that included interviews of folks experiencing housing insecurity; a DVD, including package design, marketing and promotional plans; and a live performance in the common area at the top of State Street, where Madison’s homeless community often hangs.

Rob: How can you talk about change and the achievement gap on a larger scale if you don’t have kids that are directly affected by this gap? You can say what a kid deserves and what we think. But it’s on us to meet them where they are, to get the answers we need so we can find that justice. Give these kids a chance to buy into “I can utilize this technology to make this kind of statement about homelessness.” That’s making justice.

We were fortunate to have a group of kids that were really into learning all of the areas, that was definitely huge. We had one kid that came in to learn photography. Now she’s learned about marketing and photoshopping and all this stuff. It’s a lot different than she expected, but she learned how she could utilize her skill set that she already has. And tie it into another skill set to open up her horizon to make statements on an even larger level.

Jesse: And another layer of it is that we had two teen Public Library Association interns participating in Media Academia, who were putting in five hours a day. They were learning all this stuff and helping out, and Rob is like “I’m expecting you to come back and run a Media Lab session or the next Media Academy.” And they will be coming back, and hopefully getting paid. That’s the model I’m really interested in…levels of teenagers.

Beyond Making Justice

Nancy: Jesse, can you briefly touch on how Making Justice relates to Madison Metropolitan School District program development via the Google Making Spaces initiative? First of all, what is Making Spaces?

Jesse: Making Spaces is a partnership that includes Google and ten regional hubs. The Bubbler at Madison Public Library is a Midwest hub in partnership with the Madison Metropolitan School District. We’re developing a national strategy to sustainably integrate making into schools across the United States.

Nancy: Will the program essentially diffuse makerspaces throughout the Madison Metropolitan School District?

Jesse: Yeah, but I really shy away from the term makerspace these days, it’s a really loaded term. It's defining a space, and that's not what we're trying to do. Everybody can define it differently, but for us, it’s about making space in your head for this kind of stuff, making space in your classroom, in your conversations, in your professional development. Many teachers are already doing really cool stuff. Sometimes it’s just about one extra person to collaborate with, that makes all the difference. So we’re just trying to support the faculty.

Nancy: How has Making Justice informed Making Spaces?

Jesse: The target audience for Making Justice, the equitable lens, definitely comes into play. We’re targeting the classrooms and teachers that most need enrichment. We’re really excited to be partnering with Capital High, because I know many of the kids there from Making Justice. We’re also recruiting community members to become actively involved in the program, donating their time or skills. And we’ve included community artists and activists who helped develop Making Justice as a program—like Rob and Carlos—in the professional development workshops we offer to teachers as part of Making Spaces.